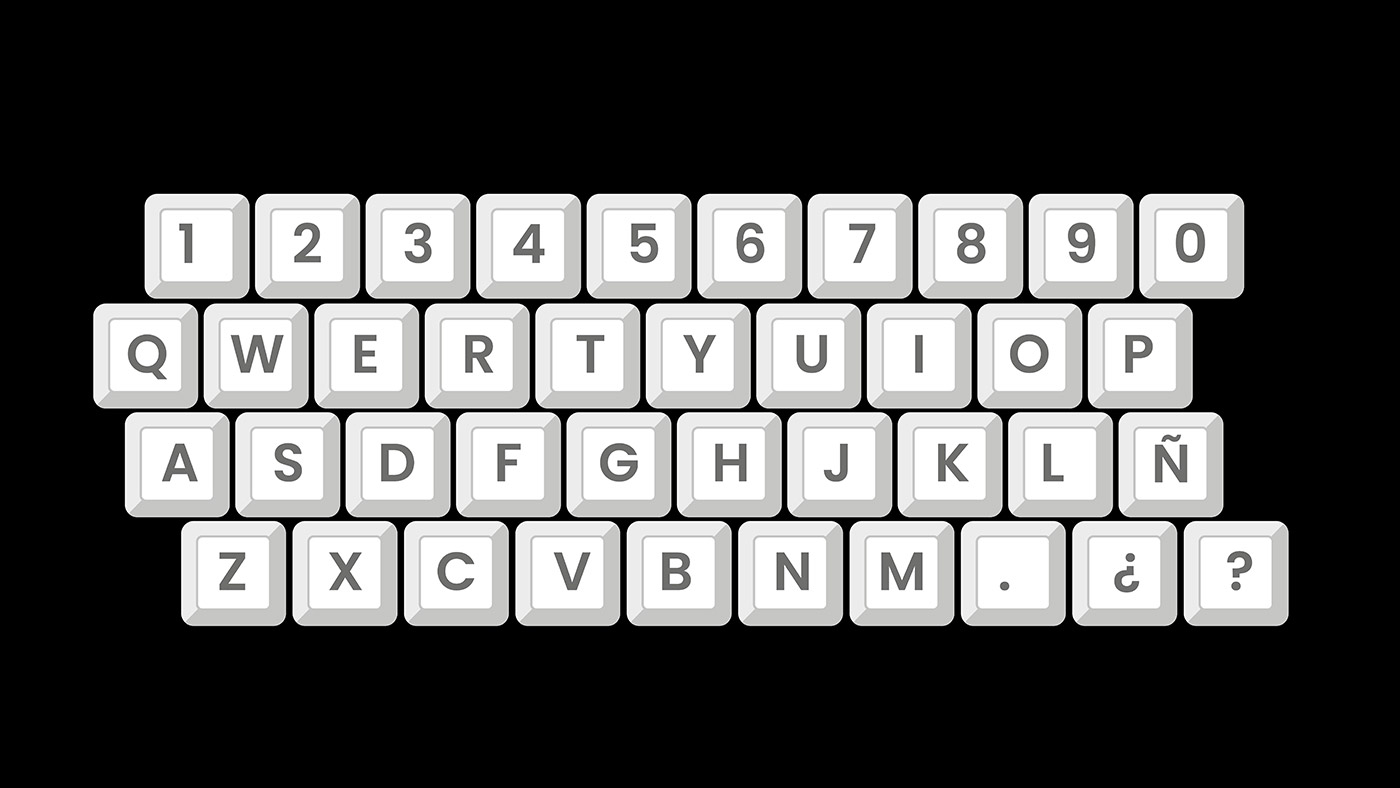

Picture this: you walk up to a keyboard for the first time in your life, ready to type your first message. Naturally, you’d expect the letters to be arranged in the familiar A-B-C-D-E order that you learned in kindergarten, right?

Instead, you’re greeted with the seemingly random Q-W-E-R-T-Y layout that has dominated keyboards for over 150 years.

It’s a question that still puzzles a lot of people: why are we still stuck with this archaic arrangement when the original reasons for its design are long obsolete? Let’s go down the rabbit hole of keyboard history, human psychology, and the stubborn nature of technological standards.

This is a different kind of article. I’m trying something new, so bear with me, come along and drop a comment with your thoughts, positive or not.

The historical baggage of QWERTY

To understand why we’re not using alphabetical keyboards, we need to travel back to 1870s when Christopher Latham Sholes created the QWERTY layout. Contrary to popular belief, QWERTY wasn’t designed to slow down typists to prevent mechanical jams – that’s actually a persistent myth that refuses to die.

The real story is more nuanced. Sholes was dealing with early typewriter mechanisms where metal typebars could collide and jam if adjacent keys were struck in rapid succession. His solution was ingenious: he analyzed letter frequency in English and strategically placed commonly used letters to minimize these mechanical conflicts. He distributed the workload between hands and positioned frequently used letters where they were easier to strike.

Here’s where it gets interesting – the QWERTY layout was actually designed to speed up typing, not slow it down. Sholes wanted to create the first keyboard layout that was actually practical for professional use, moving beyond the simple alphabetical arrangements that early demonstration typewriters used.

Why ABCDE keyboards are actually terrible

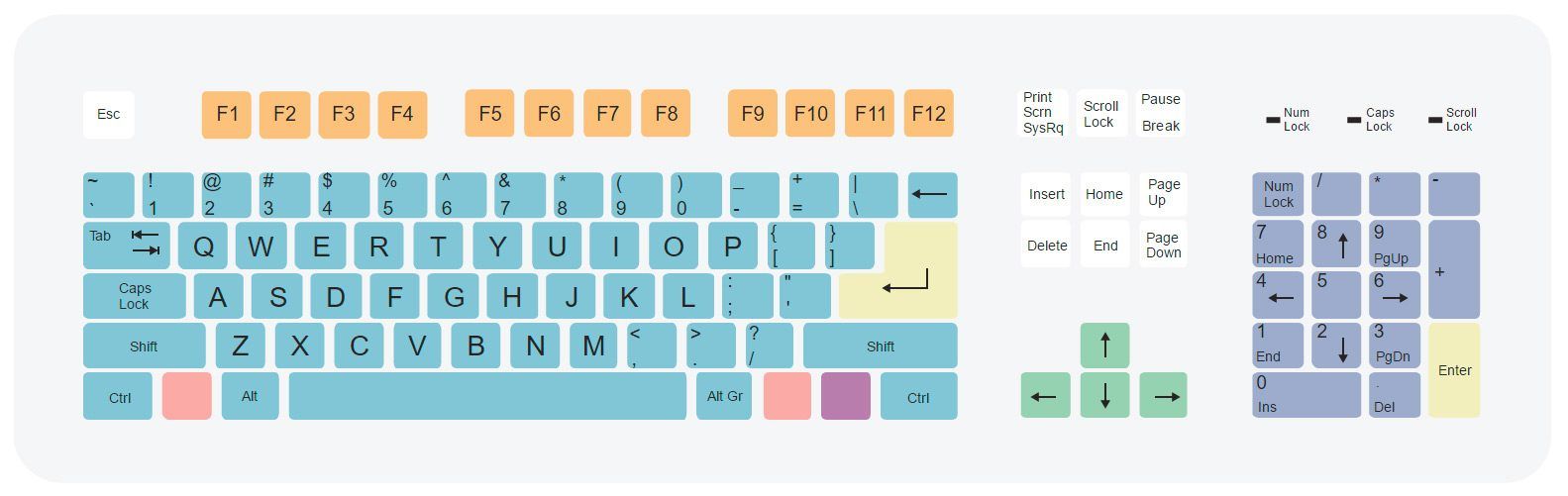

Now, you might think, “Surely alphabetical order would be more intuitive?” Well, here’s where things get counterintuitive. Some keyboard enthusiasts ran the ABCDE layout through modern analysis software, and the results were pretty surprising.

In an alphabetical layout, your poor left pinky – the weakest finger for most people – would handle a whopping 16.43% of the typing workload. Compare that to QWERTY’s more reasonable 7.94%. Your right pinky would also suffer, taking on 7.73% compared to QWERTY’s 3.34%. That’s a recipe for finger fatigue and repetitive strain injuries.

But it gets worse. Remember how T and A are the second and third most common letters in English? In an ABCDE layout, they’d both be typed by your left pinky, positioned at the maximum possible distance from each other. Try rapidly typing “QZQZQZQZ” and you’ll get a taste of how painful common English words would become.

The ergonomic nightmare doesn’t stop there. Take the letter T – the second most frequent letter in English – and imagine having to reach for it with your weakest finger on the bottom row (where Z sits on QWERTY). Your hands would be screaming for mercy after a few paragraphs.

The psychology of familiarity and muscle memory

Here’s where human psychology enters the picture. I’ve been touch-typing on QWERTY keyboards for decades, and like millions of others, I can type without looking at the keys. My fingers know exactly where each letter lives, creating what feels like a direct connection between my thoughts and the screen.

Muscle memory is incredibly powerful. Sometimes I feel like I can literally touch-type while watching TV, mostly not looking at the screen as I write. I can even notice and correct errors by touch because incorrect keystrokes feel wrong.

Asking the world’s typists to abandon this deeply ingrained muscle memory for a theoretically better system is like asking everyone to drive on the opposite side of the road, but 10 times harder. The transition costs are enormous, and the benefits would need to be absolutely revolutionary to justify the trouble. And that’s just not the case.

The network effects and institutional inertia

The QWERTY layout benefits from what economists call “network effects” – the more people who use it, the more valuable it becomes for everyone. Every keyboard manufacturer, every typing teacher, every office worker, and every computer programmer operates within this shared standard.

Imagine if your company decided to switch to alphabetical keyboards tomorrow. Suddenly, you couldn’t efficiently use your colleagues’ computers, public terminals would become frustrating obstacles, and any temporary worker would struggle with your systems. The interconnected nature of our digital world makes individual switches incredibly costly.

Educational institutions have built their entire typing curricula around QWERTY. Businesses have invested millions in training employees. Software interfaces assume QWERTY shortcuts (like Ctrl+C being easily accessible). The entire ecosystem is optimized around this 150-year-old standard.

Alternative layouts: the road not taken

The fascinating thing is that we do have scientifically designed alternatives that put QWERTY to shame. The Dvorak layout, created in the 1930s, places the most common English letters on the middle row under your strongest fingers. Colemak offers a more modern approach that minimizes finger movement while keeping some QWERTY familiarity for shortcuts.

These layouts have passionate advocates who swear by their superior ergonomics and efficiency. Some claim typing speeds of 120+ words per minute with less finger strain. Yet they remain niche curiosities, used by perhaps a fraction of a percent of the typing population.

Why? Because the benefits, while real, aren’t dramatic enough to overcome the switching costs. Studies have shown that while alternative layouts may offer advantages, QWERTY is “good enough” – close enough to optimal that the improvement doesn’t justify the massive disruption of changing.

Don’t get me wrong, there are plenty other semi-popular layouts like AZERTY, QWERTZ, adapted from QWERTY to serve French, German speakers, but they’re still QWERTY at core. And no, these weird keyboard layouts are not going to replace the king anytime soon.

The smartphone revolution and missed opportunities

When smartphones emerged, we had a golden opportunity to rethink keyboard layouts. Early phones with physical keyboards stuck with QWERTY, but the rise of touchscreens could have been our chance to start fresh.

Unfortunately, the developers of virtual keyboards faced a crucial decision: make typing familiar for existing computer users, or optimize for touch input. They chose familiarity, and now QWERTY dominates our pocket computers too.

Some niche applications do use alphabetical layouts – like T9 TV remote controls for entering text, old dubm phones, or certain accessibility interfaces. But these are typically for occasional use, not the intensive typing that would benefit from optimization.

The myth of obsolescence

Here’s where the conversation gets nuanced. While the original mechanical constraints that shaped QWERTY are indeed obsolete, many of its design principles remain relevant. The distribution of work between hands, the positioning of common letters in accessible locations, and the separation of frequently paired letters still matter for ergonomics and typing efficiency.

Modern research has shown that QWERTY, despite its age, is actually quite well-designed. It’s not perfect, but it’s surprisingly close to optimal for English typing. The idea that it was deliberately designed to slow down typists is not just wrong – it’s backwards. Sholes was trying to create the fastest practical layout possible with the constraints he faced.

Real-world encounters with alphabetical keyboards

Some people do encounter alphabetical keyboards in their daily lives. Some mention the frustration of using ABC layouts on parking payment machines: “I find [them] surprisingly hard to use… I can type very fast on a QWERTY keyboard, but hunt and peck painfully slowly on alphabetical ones.”

This experience highlights a crucial point: even for simple tasks, the unfamiliarity of alphabetical layouts can be jarring for people trained on QWERTY. The cognitive load of visually searching for letters in alphabetical order, ironically, can be higher than recalling the learned positions of QWERTY keys.

The future of keyboard layouts

So where does this leave us? Are we doomed to stick with a 150-year-old standard forever? Not necessarily. The rise of voice recognition, gesture input, and AI-powered text prediction might eventually make physical keyboard layouts less relevant.

But for the foreseeable future, QWERTY’s dominance seems secure. The costs of switching are simply too high (monetary and cognitive), and the benefits too marginal, for any alternative to gain widespread adoption. Even superior layouts like Dvorak or Colemak remain curiosities for enthusiasts rather than mainstream solutions.

What’s interesting is that we’re seeing innovation in other areas – ergonomic keyboard shapes, programmable layouts, and specialized keyboards for gaming or coding. The future might not be about changing the letter arrangement, but about adapting the physical keyboard to better suit our hands and tasks.

The verdict on ABCDE keyboards

It’s time to draw the conclusion. The answer to “why not ABCDE keyboards?” is clear: they would actually make typing worse, not better. The alphabetical order that seems logical for learning letters doesn’t translate to efficient finger movement or ergonomic typing.

QWERTY, despite its flaws and outdated origins, represents a remarkably successful solution to the complex problem of mapping language to human hands. It’s not perfect, but it’s proven itself over nearly 150 years of evolution and adaptation.

The real lesson here isn’t about keyboards at all – it’s about how technological standards become entrenched, how switching costs can preserve suboptimal solutions, and how “obvious” improvements often have hidden drawbacks that only become apparent under closer examination.

Conclusion: embracing imperfect standards

The story of QWERTY vs. ABCDE keyboards is ultimately a story about human systems, not just technology. We live with imperfect standards because perfection isn’t always worth the cost of change. Sometimes “good enough” really is good enough, especially when millions of people have built their skills around that standard.

The next time you sit down at your keyboard, take a moment to appreciate the complex history beneath your fingertips. You’re using a layout that emerged from 19th-century mechanical constraints, survived the transition to electronics, and continues to evolve in our digital age.

What do you think? Have you ever tried alternative keyboard layouts, or do you have strong feelings about the tyranny of QWERTY? I’d love to hear about your typing experiences and whether you think we’ll ever see a major shift in keyboard standards.

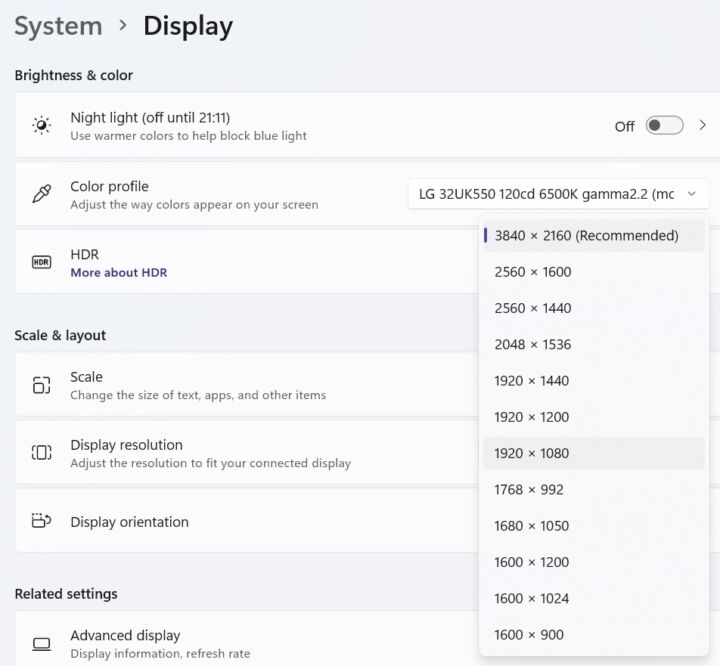

Personally, I’ll stick with my beloved TKL (80%) QWERTY keyboard that I’ve reviewed here. It’s still the end game keyboard for me, with a little help from the wireless numberpad I’ve added to the left, so that my right hand sits closer to my mouse. You see, it’s all about the ergonomics.